Rating: 5/5

Righteousness. The word may have lost its true meaning in the contemporary age, when mass murderers have a right to defend and killing children is a strategy. The past was not as smudged. Socrates, no less, emphasized that righteousness must be the supreme priority. So did Dr. APJ Abdul Kalam, the missile man of India. After reading Chinua Achebe’s masterpiece, Things Fall Apart, the question troubling me is about the cost of righteousness.

Things Fall Apart is arguably the greatest work of postcolonial fiction, and easily the greatest African novel of the 20th century. The novel sucks you in from the very first page, then holds you by your throat till the very end. And when it ends, there’s a void left in the reader, an uneasiness beyond words, a shiver beyond expression. I have had a similar experience twice before, after reading Orwell’s 1984 and Dostoevsky’s The Idiot. That’s something to say about Achebe’s penmanship!

Things Fall Apart – The African Tale

The Fall Apart is a simple story of pre-colonial Nigeria. It’s a tale of a tribesmen, for whom three things matter the most – a good farm yield, a solid social life, and being “righteous” in their ways. What they considered righteous is questionable, though the fact that they were honest in their belief is absolute. Okonkwo, the protagonist, is a great warrior of the tribe and a man who rules his household with an iron fist. Being strong and “righteous” is what pleases him. His biggest fear – Nwoye, his eldest son, would grow to become a weak and “unmanly” man like his father, Unoka.

The story begins with Okonkwo’s rise from a farm labourer to one of the most respected leaders of his clan, Umuofia. Life in tribal Africa is slow, where people live their lives moon to moon, season to season, harvest to harvest. The summer is harsh, the rains plenty, and the harvest abundant for those willing to put in the hard days. Okonkwo despises those with “soft” efforts and often cribs about how the younger generation has become weak and lazy, something that oldmen of all ages opine about the young.

In between moons, rains, and the harvest, Achebe portrays that vibrant African culture in its truest spirit. From women decorating their bodies to men wrestling for glory, the author has taken a no-holds-barred approach. The blood of Things Fall Apart is the theology of the tribesmen, which has gods, spirits, ghosts, omens, shamans, and rituals, a lot of rituals.

And then came the white man, with the message of the Lord – and the colonial army along with him. Suddenly, tribesmen fighting each other for glory, lost in their tradition, holding on to the spirits of their forefathers, were treated as pagans. With their beliefs questioned, sons converted, and outcasts sheltered by the Church, Okonkwo and his tribesmen are subjected to indignity and humiliation. That is where Chinua Achebe leaves his reader, in agony and agitation.

Things Fall Apart, Bit by Bit – The Broken Protagonist

Okonkwo is a strong, “righteous” man who works hard to provide for his family. He is the greatest warrior alive, never shying away from a kill for the “right” cause. Yet, he is insecure, mostly of being seen as a weak man like his father. Okonkwo does things that twists the reader’s guts – beats his wives to keep them in line, willing to skin his boy for not being man enough. You almost hate him. Almost, because you realise that deep down, Okonkwo is regretful for his actions and whatever he does is due to peer pressure of being a great leader, a great warrior.

His life begins with a lazy, drunkard father, who lost his life to debt and drinking. Okonkwo builds his life from scratch, working with blood and sweat from one harvest season to another. Times change, as Okonkwo and his family are exiled from Umuofia for seven years. The man becomes silent, but not subdued, and instead of giving up, prepares for his return. And when he does, he is left disappointed. The white man and his religion have spread like creepers on a giant tree. The men of the clan are divided, fathers and sons fighting on opposite sides. And the worst, the leaders of the clan have lost courage and faith in their gods, compelling him to choose diplomacy over war, cowardice over revenge. And there, in his days of decline, the hatred for him turns into pity first, and then into sympathy.

Things Fall Apart, One Child at a Time – The Cursed Children of Africa

If you’ve been punched in your gut, you’ll relate what I’m about to write. There’s a short story within this novel, like a Shakespearen tragedy. The child’s name was Ikemefuna. His crime – his father killed an Umuofia girl. His punishment – to leave his mother and little sister to live in Umuofia. Okonkwo takes the child in, feeds him like his own children, treats him like his own son. Three years go by, and he becomes the son that Okonkwo wanted Nwoye to be. And then, one fine day, the final phase of his punishment descends, being murdered by the man he called father. Just like that. Though the death was instant, the impact on the reader will be for years to come.

Then there are the twins, several of them. Unnamed, unloved, discarded in the evil jungle. Their crime – being born in pairs. The moment they take their first breaths, they are snatched from their mothers, as it is only “righteous” to follow the spiritual protocol to deal with the devils. Mothers wept in silence, dared not let their husbands know. The cries of the twins die with the night, when mother earth sucks them in her womb.

Things Fall Apart, When the White Man Comes – The Dogma of Colonial Democracy

The white man came to the villages of Africa, with a new religion and civilization. He came and told the people of Umuofia how wrong they were and that they needed reform. On its face, it seems a righteous act. Why shouldn’t the “noble” man stop the people of Umuofia from killing their children and beating their wives! But behind the priest, came the man with a gun and an army, under the supreme command of the white queen. His mission? Implant civility in the wildlings of Africa, either through the priest or through the gun.

Democracy is a crazy concept. The Oxford dictionary defines democracy as, “a political system that allows the citizens to participate in political decision‐making, or to elect representatives to government bodies.” When you look at the tribes of Africa, that was exactly what they did. They chose their elders, and the chosen representatives made decisions for their communities. In fact, the system was so meritocratic, that Okonkwo, the son of a poor drunkard who left behind poverty and debt, worked hard and became a leader chosen by the people. Sounds like the American dream, doesn’t it?

The “righteous” men, however, did not want African democracy. They wanted the rule of the English monarchy, which itself is not so meritocratic. And they do what they did best – colonize, humiliate, and kill. Okonkwo refuses to suffer the humiliation. The greatest wrestler of Umuofia fights back, and refuses to bow before by the white man. Regardless of his crimes and sins, the reader will sympathise with Okonkwo and the elders of Umuofia.

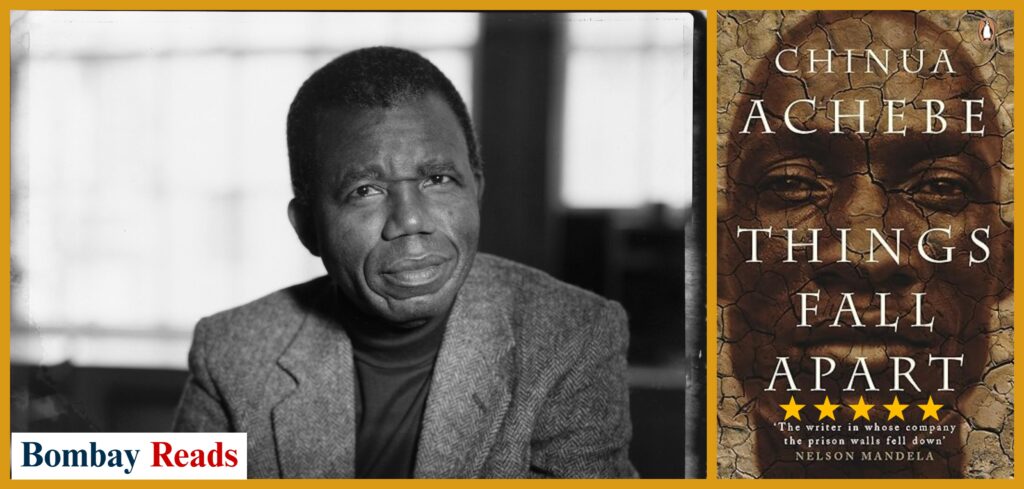

Chinua Achebe – A Master Storyteller

Things Fall Apart is the first African novel that I’ve read, and I could not have a better start. Chinua Achebe has taken great pains to keep the cultural authenticity intact. From the very first page, I got sucked into the world of Umuofia, and felt like I was witnessing Okonkwo’s journey. I had my heart in my mouth on multiple occasions. That said, Achebe’s greatest strength, in my humble opinion, is the simplicity he maintains.

Things never get too dramatic or too emotional. He never lets the reader ponder over life’s grievances too much. In a subtle way, the novel makes the fallen get up quickly and move on with life every time they fall. Another great attribute in Achebe’s writing is how effortlessly he puts across tragic events and statements. There’s one sentence, “I think this one will live.” It seems like a simple conversation between two women of the tribe. With context, though, my eyes popped out, even without Achebe trying it. That, dear readers, is greatness.

Chinua Achebe was born in Ogidi, Nigeria, on 16th November, 1930. He was a poet, novelist, and critic, and is widely regarded as the greatest African novelist of all time. He received 30 honorary degrees from universities across the globe, including Harvard, Brown, and Datrmouth. Achebe became a Goodwill Ambassador of the United Nations Population Fund in 1999. He won the International Booker Prize in 2007, in addition to several national and international awards.

Chinua Achebe passed away on 21st March, 2013, in Boston, Massachusetts, United States.

Editor – Bombay Reads

Student at the University of Portsmouth, United Kingdom

Content Writer